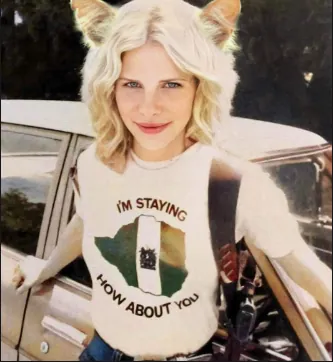

A piece I wrote on one of the most fascinating and incredible thriftstore finds I've ever stumbled upon.

The Edwardians and Victorians were not like us, they believed in a nobility of their political class that's almost impossible to understand or relate to, and that believe, that attribution of nobility is tied up with something even more mysterious: their belief in the fundamental nobility of rhetoric.

Still not sure entirely how I feel about this, or how sure I am of my conclusions but this has had me spellbound in fascination and so I wrote about it.

Jump in the discussion.

No email address required.

Notes -

Great piece.

I've found I prefer older translations of the classics to newer translations. I've read both Garth's Ovid and Mandelbaum's, the latter in class the former for pleasure. I got so much more out of the former, even though the latter is (according to the academics I know who could actually read it in the original) far more accurate to the original meaning. This piece from the Paris Review actually asks a lot of the same questions comparing different verse translations to a different modern prose translation

Modern Prose:

Old Verse, by Dryden:

t>he monsters of the deep now take their place.

Ditto the Iliad. Pope's verse translation:

And a more modern prose translation by Kline:

I understand the value of accuracy in modern academic translations*, that they better capture the word-for-word meaning of the original text. But so much of the spirit is lost when the translator clearly does not believe in the text in the way the original writer did. The modern translator of Homer does not believe in the glory of battle, the modern translator of Ovid does not understand the playfulness of the gods to be a thing of beauty. The modern translations are drab, or they view the events of the stories as horrors. Homer and Ovid did not view their stories that way, and that meaning is more important than the syntax.

The spirit of the work is an unbroken chain of interpretation from Homer and Ovid to Pope and Dryden, but it is lost in a modern Classics department. I was lucky enough that my professors in undergrad at least had a hint of that, at least understood enough of it from their professors to be able to give a taste of it before returning to questions of "Queering the authorship" or whatever the fuck. The next generation of Classics students may not even get that. They may be taught by Postmodernists who were taught by Postmodernists, they will know no other way to look at the Iliad than through a queer Feminist of Color lens, and something will be lost. I recently completed this lecture course on the Early Middle Ages, at one point when discussing the discursive concept of The Dark Ages, professor Freedman suggests that we are reentering a new dark ages if we define a dark age by knowledge of Homer. The Greeks and Romans knew Homer, the dark ages lost that knowledge, the Renaissance and Enlightenment regained it, we are losing it once again.

*A second, equally facile, argument is made that the archaisms of the old translations hold them back, make it difficult for ordinary readers to enjoy them. This is often used as a reason why the Bible must be endlessly retranslated and updated. It's enough to make one wish to return to the Latin Mass, perhaps I should finally learn it in full. It is precisely classic literature that grounds a language, whether it is the Greeks and Homer, or the English and Shakespeare. We should reach back for these works while we can still read them with only a minimum of effort, and preserve them so that our heritage as modern English speakers can stretch from the Elizabethan to today. If we let our ability to read the Classics slip away, if we need translations of Shakespeare and Milton and Pope, we will lose that unbroken heritage, our children will be unable to regain it.

If you could recommend one chapter of one translation of one classic (the Odyssey or any other) that conveys the spirit of the original text, what would you choose?

Book X of the Metamorphoses, in the Garth translation I recommended above. It covers Orpheus and Eurydice, Pygmalion, Venus and Adonis, Atalanta; along with a pile of others. Orpheus and Adonis are key myths to understanding the classical world, they tend to get skipped over or shortchanged in favor of the Sword and Sandals stuff like Hercules and Achilles in popular adaptations but they were hugely important religious stories. It also gives a really good feel for Ovid's method, in that it mixes with stories like Atalanta that are playful, Pygmailion that are meaningful but small time, and stories that are profoundly meaningful and religiously significant like Orpheus. It's light and beautiful and gorgeous and fun and important.

More options

Context Copy link

More options

Context Copy link

More options

Context Copy link