The Wednesday Wellness threads are meant to encourage users to ask for and provide advice and motivation to improve their lives. It isn't intended as a 'containment thread' and any content which could go here could instead be posted in its own thread. You could post:

-

Requests for advice and / or encouragement. On basically any topic and for any scale of problem.

-

Updates to let us know how you are doing. This provides valuable feedback on past advice / encouragement and will hopefully make people feel a little more motivated to follow through. If you want to be reminded to post your update, see the post titled 'update reminders', below.

-

Advice. This can be in response to a request for advice or just something that you think could be generally useful for many people here.

-

Encouragement. Probably best directed at specific users, but if you feel like just encouraging people in general I don't think anyone is going to object. I don't think I really need to say this, but just to be clear; encouragement should have a generally positive tone and not shame people (if people feel that shame might be an effective tool for motivating people, please discuss this so we can form a group consensus on how to use it rather than just trying it).

As we roll into the end of 2025 I think it'd be good to have a thread in the rationalist tradition of putting down predictions with confidence ratings for 2026. Feel free to take the my list and make your own predictions off them and/or add new things to predict and I'll add them to the op with my own prediction. I'll put my predictions in spoilers at the end. Feel free to critique other people's predictions but for fairness if you're going to say someone's prediction is wrong you should supply your own odds as well. Of course let me know if any of these categories are under defined.

By December 31st 2026

AI:

- Yudkowski declares AGI/ASI Achieved

- We have federal regulation passed through congress to regulate AI

- Anthropic announces IPO

- A Chinese model is released that is widely considered to be the best coding model(not just on price per token)

- AI System wins an award for a significant contribution in mathematics

- A lab releases a fully autonomous drop-in worker agent that at least five fortune 200 companies implement

- OpenAI revenue exceeds $30 billion

- A frontier lab experiences a security incident that requires public disclosure

US Domestic politics:

- Democrats have a majority in the House

- Democrats have a majority in the Senate

- Trump Approval rating exceeds 50% at any point

- A government shutdown exceeds 14 days

- total deportation in 2026 exceed 500k

- Mamadani implements fare free busses city wide

- Mamdani implements at least three state run grocery stores

- Trump is impeached

- A Major political figure is assassinated(Congress/SCOTUS Judge/Executive cabinet member)

Wars:

- Israel-palestine conflict reignites

- Ukraine war ceasefire lasts greater than 30 days at any point

- China invades Taiwan

- US officially at war with Venezuela at any point

China:

- Official GDP growth below 4%

- Youth unemployment (16-24) reported above 15% at any point in 2026

- Major Chinese property developer (top 20) enters formal bankruptcy

- SMIC achieves volume production at 5nm or below

Economics:

- US enters recession (2 consecutive quarters negative GDP growth)

- S&P 500 higher on 12/31/26 than 12/31/25

- US unemployment rate exceeds 5% at any point

- Bitcoin above $150k at any point

- YoY inflation exceeds 4%

Technology:

- Starship upper stage (Ship) successfully lands (caught or propulsive landing)

- Blue Origin New Glenn completes 5+ successful launches

- Tesla releases vehicle with SAE Level 4 autonomy to consumers

- US approves new nuclear reactor construction (not SMR)

This thread is for anyone working on personal projects to share their progress, and hold themselves somewhat accountable to a group of peers.

Post your project, your progress from last week, and what you hope to accomplish this week.

If you want to be pinged with a reminder asking about your project, let me know, and I'll harass you each week until you cancel the service

This post is an unscientific clickbait for people who want the flattering kudos and ego-stroke that come from a minor accolade on this corner of the internet.

This post is a grab-bag of meta-observations on the sort of tactics or techniques one might use to start building a positive reputation in a reputation-economy moderation forum.

This post is a completely selfish effort to get other people to write more of the sort of posts I like to read.

Any of these reasons could be true. None of mine are noble. But like the rule of three, if it works for thee…

///

Why Should You Believe Anything In This List?

Let’s just start by saying you shouldn’t, and instead read on with healthy level of indulgence. I am a stranger on the internet with a history of opinions and a whole host of pejoratives earned in return. I make no claim to insider insights, impressive metrics, or special profession.

On the other hand, personal credibility can help. At the same time, it is hard to appeal to yourself without appearing a cad as well as a braggart. Instead, let’s just settle for that I have written some AAQCs, and read even more from others.

Hopefully, the following claims can hopefully stand on their own, with some appropriate caveats. This is a list for organization’s sake, not a claim of all relevant factors. I am (trying) to keep it relatively short per claim. None of this guarantees you will get an AAQC. Fair enough?

///

Agenda

This list of fifteen tips will be organized in four parts.

Part One: Social Engineering From The Start

1: Moderator Interests

2: Interested Audiences

3: You (Yes You)

Part Two: Structure and Formatting

4: Fundamentals Always Apply

5: Depth vs Breadth vs Brevity

6: Organization & Visualization

Part Three: Traps to Avoid

7: The Diss Post

8: The Typical Rut

9: The AI Assist

Part Four: Topics Of Common Interest (And Honorable Examples)

10: Subject Matter Experts

11: Timelines & Narratives

12: Global Political Developments

13: Popular Culture Media

14: People & Places

15: Human Experience Stories

Conclusion With All The Tips

///

Part One: Social Engineering From The Start

There is a relatively simple social formula for getting an AAQC:

[YOUR AAQC] = [(Moderator Accepted) AND (Not Moderator Veto)] AND [Nominated by Mottizan] AND [Written by YOU]

Recognizing the implications and interests of these three groups can help you get to the door, or at least not exclude you from consideration.

/

1: Moderator Interests

Tip 1: Moderators are the last and most obvious screening party. Less obvious is that they screen in two ways.

The last stage of every AAQC is a mod formatting the post they will make of the AAQCs they have selected. Every AAQC is nominated via the same report button used to tag potential troublemakers for consideration. While @naraburns leads the process and posts the product, IIRC other mods in the past have mentioned they all can see the report folders, and thus greater opportunity to opine, during the list’s creation and tailoring phase. While different mods may have no influence on the process, others might functionally, if not formally, present a veto.

This does not mean you should try to appeal to moderators too directly. naraburns don’t like no brown noser. It does mean you should try to understand what they would oppose, or what they want to promote, and why. naraburns has been open that they view AAQCs not as a mark of accuracy, but as rewarding people for a positive contribution to the Motte community. What makes something a positive contribution? You can find more of Nara’s modding philosophy here. Other mods have their own. When the time comes to narrow down all the AAQC reports to a final list, those philosophies are what influence which of the variously deserving posts make the cut, and which are cut.

These perspectives collectively lead towards a general point- moderators view AAQCs as a way to nudge The Motte towards the sort of forum they would like it to be. They are more likely to advance an AAQC they view as contributing that that ‘better,’ even if they disagree with it on a personal level. They are not going to proactively advance nominations they feel detract from the ethos or health of the Motte. Though differing opinions could lead to different conclusions of what qualifies as what, from an AAQC-seeking perspective moderator views are a reality you need to navigate around.

/

2: Interested Audiences

Tip 2: Some of your fellow Mottizans must find your post interesting. Preferably serial nominators.

If moderators are screening for impact, it is the rest of the Motte which actually nominates based on interest. Unless you are so desperate that you would use a sock puppet to nominate yourself, your AAQC depends on someone else thinking it is interesting enough to bother pressing the few buttons to report it. No one does this for the things that bore (or frustrate) them.

This does not mean that you need to appeal to many Motte posters. While the number of nominations may sway a moderator’s consideration, a post nominated by just one person is just as in the bin as a post nominated by one hundred. The bigger impact of popularity-posting is probably/possibly that someone bothers to nominate it in the first place. If each person who likes a post has a 1-in-X chance to actually nominate, then someone who appeals to X people has a much higher chance of getting nominated than someone who appeals to less-than-X.

But in practice, or typical human psychology, not all audience members vote equally. Call this a guess, but were I a betting person I’d bet that people tend to nominate far, far more than others, for the same sort of reasons that some people post more, or downvote more, or so on. Granted, this is probably topical rather than general- it is less that these people nominate for all topics, but their topics of particular interest. These purely hypothetical ‘super nominators’ are your ‘real’ target audience if you seek an AAQC nomination. Writing to the topics that interest them enough to nominate is your ‘hack,’ whether that topic is AI, academia, geopolitics, or whatever.

/

3: You (Yes You)

Tip 3: You are a Mottizan too. Write about what interests you.

Every AAQC ever approved first had to be written. Inverted, no one has ever gotten an AAQC for a post they did not write. You (yes you) are more critical than any other person in the process. No mod can endorse a response you did not post; no audience be interested in an argument you did not make.

This reinforces the point about writing to the interests of those who matter. It is not just the people who nominate an AAQC who must be interested. You are people too. You have to be interested enough to develop the post in the first place. Yes, you could approach a deliberate AAQC as if you were authoring a book report. Book reviews are a reasonably predictable way to get an AAQCs, if that is all you care about. But if you are on the Motte, you are at least a young adult, and adults have competing priorities and interests that will tend to win over unnecessary book reports for interweb audiences. AAQCs are kudos, not paychecks. There is a reason that most Mottizans who go writing for Substack stop writing much here.

This is why it is important to write about things that interest you. Your own interest is what corresponds with the other factors that cultivate interest in others. Passion can lead to more effort and exposition that can reveal new and novel things to the audience. Positivity encourages positive interest, contrasting with passivity and doomerism more likely to stir apathy to hitting that report button. People having fun nerding out encourages other people having fun nerding out with them, which is the sort of good-faith discussion that the mods want to encourage.

///

Part Two: Structure and Formatting

If you are going through the effort of writing an effort post with the hope of an AAQC, put in that little bit more to make it easier for the audience to digest. Many in the audience have limited time and less patience to scroll through a never-ending narrative. Giving a sense of progression can help the audience hold out to the end and thus get to that report button which you want them to push.

/

4: Fundamentals Always Apply

Tip 4: Basic principles of writing (almost) always apply.

AAQCs are not college essays, and the idiosyncrasies of informalities add to the quality. That said, the things that would make for a bad paper can reduce a ‘quality’ contribution to merely ‘interesting.’ A lot of this is surface-level cleanup, like using a spell checker, making sure you did not leave incomplete sentences as you were trying to organize thoughts, or overly long paragraphs. (Yes, I am aware of the irony. There is slack.)

The most important shared principle is hooking the audience’s interest by telling them what you are going to tell them as early as possible. The Motte weekly threads have over a thousand posts a week, more than is feasible to read. People skimming will read what looks interesting. If they cannot tell that within the first few lines, they are as liable to skip it as something that looks uninteresting from the start. If you can do this with a suitable quip that the mods can use for your AAQC tagline, all the better.

There are exceptions to everything, however, and having a mastery of fundamentals is what gives you the judgement of when and how to deviate. Grammar checkers are good, but AI slop that bores people is often excellent on a technical level… so having technically incorrect grammar (like …s or (parentheses clauses)) can increase the informality. Telling the audience what you are telling them is good, but sometimes a bait-and-switch for demonstration purposes depends on you not doing so. Such techniques are easy to misuse, and can annoy some, but performed well they can deviate from the norm enough to stand out and be called out.

/

5: Depth vs Breadth vs Brevity

Tip 5: Know whether you are trying to go deep or broad, and then be brief on the other part.

AAQCs do not have to be long, but they tend to be. It takes a bit of space to lay out enough thoughts to be far enough outside the norm to stand out. It is easier to do that by adding more in unique ways than in trying to rearrange a smaller set of text in ways that will pass the social selection tests. However, too much text is boring, and being both deep and broad leads to exponentially more text. If you cannot be brief in general, be brief on either depth or breadth.

Depth in AAQCs tends to come from paying a lot of attention to a relatively narrow context. This allows exploring the nuance of a specific subject, series of events, or perspective. It is rarely well suited to grand theories of the world, but it does not need to be. ‘Depth’ AAQCs are probably the easiest in terms of effort, since they can come from your individual subject matter expertise in a particular subject, but the hardest to stand out in if your area of expertise is relatively common. Brevity in depth comes from pruning the tangents or rabbit holes that would lead away from the focus.

Breadth in AAQCs tends to come from tying together a lot of different fields to form a coherent narrative. This is much harder both because there are more areas your area of competence to trip over, but also because any one of these fields could provide its own ‘depth’ effort-post. ‘Breadth’ AAQCs are probably the hardest in terms of effort, since you must bring in more topics, but the easiest to stand out from people who do not / cannot do it as well. Brevity in breadth comes from concisely summarizing new actors or factors as able, so that you can cover the effects they had rather than the factor itself.

/

6: Organization & Visualization

Tip 6: Write in a way that makes it clear where you are starting, where you are going, and how far along the way you are.

Humans are superficial visually-oriented creatures, and appearances matter. In so much that the cardinal sin of AAQCs is to be boring, few things bore as much of seemingly endless walls of text. While tip four focused on hooking people with your topic, and tip five focused on scoping the topic, this tip acknowledges the dark art of all true Mottizans- PRESENTATION!

With moderation and deliberate effort, you can make the exact same text grab (and keep) attention if you use text format to draw attention not words later in the paragraph.. It’s not just that bold is for emphasis, or italics allow an alternative insinuation if you know what I mean, or that the Motte’s blue text external links are you sign of something useful, interesting, or amusing,

or all three. (There is an AAQC to be made about that one, I swear.) Those are characterizations of how the text formatting is used by an author. The utility for the author vis-à-vis the reader is easier. Even if the reader is skimming, they will notice a key point buried in a paragraph if it is well formatted. That notice may draw interest, and attention, to stay engaged. Just… don’t overdo it, or it loses the effect.

Finally, consider a chapter break system between the distinct arguments in longer effort posts. In shorter posts, you can use bolded words as ‘chapter titles,’ which makes it obvious when a new topic starts. In a longer post, using a page break at the end provides the scrollers that indicate that the previous topic is over, and the new stuff may be more interesting. Personally, I like to use / and /// as minor and major transitions, so that people can know if they are still on the same general topic or a larger change of topics.

///

Part Three: Traps to Avoid

The other side of learning the principles behind AAQCs is recognizing the tendencies that undercut it. This returns to the previous point that AAQCs are a mod tool for highlighting and commending posts that shape the Motte towards a certain sort of discourse. By extension, the sort of posts which go against that will typically not make the cut.

/

7: The Diss Post

Tip 7: Writing in insults is a way to write yourself out of an AAQC.

A key ethos of the Motte as a project is to optimize for light, not heat. One way of interpreting this is that people are expected to disagree but are moderated on how they do so. Whether it is booing the outgroup of your political opponents in a post, or insulting the other poster you are responding to, carrying on an argument too aggressively is a quick way to scuttle any AAQC post.

This does not mean that critiques, even personal critiques, are off limits. You can get AAQCs for explaining why people hate certain athletes, outright calling an academic study bullshit, or even takedowns on the bad faith troll arguments of other Motte posters. The Motte is named for a military metaphor for a reason, and it is not because the forum is expected to be agreeable and harmonious.

But as much as Amadan’s AAQC takedown of Darwin has practically become a Motte legend for how the passion and fury behind the direct criticism led Darwin to abandon the guesswho account and the Darwin association entirely, it was the exception and not a norm. It was exceptional because, despite the anger behind it, the personal critiques still centered on the target’s own arguments and behavior associated with pushing those arguments. Most posts lack that distinction, or that balance of historical context, to manage that. If you want an AAQC consideration in the context of an argument, to publicize your position and get some sort of last word in the argument, take down the argument, not the arguer.

/

8: The Typical Rut

Tip 8: Build a reputation of being more than a single-issue poster by posting on more than a small cluster of issues.

Several previous points emphasized that the Motte AAQCs are part of both a reputation economy and an interest economy. Part of being interesting is novelty, so people do not grow bored and dismissive if your argument pattern matches their predictions of you. Like a dish of your favored food, something that is enjoyable at first, becomes a lot less enjoyable if over-indulged. For AAQCs centered on ‘depth,’ plumbing the same narrow cluster of themes gradually grows stale.

This is an issue with single-issues posters share, whether you feel their issue is a good one or not. Someone with a new take on an issue is unique once, but there are only so many variations on the theme before it is stale. People with less popular issues, such as joo-posters who try to frame even nominally different topics in terms of malign influence, tread the same rut point to the point it is practically a game to spot the fixation. The issue for AAQC qualification is not whether the issue is morally good or bad, but whether it is tiring and trite.

The antidote to this sort of typecasting is to share the breadth of views that make you a character rather than a caricature. Not only does a diversity of opinions leave people guessing what direction you will take this time, but it enables the sort of ‘breadth’ AAQCs that have a lot more chance to combine things in novel ways. You don’t have to abandon your interests either- just use your starting rut as the initial path to a topic less traveled, and eventually you will be seen as a person with a world view as opposed to a single view point that could be machine generated.

/

9: The AI Assist

Tip 9: The judgement of whether AI improves the quality of your post rests with the audience, not you.

This is not a point about whether AI tools can help you write better. This is not a position on whether AI assistance should matter. This is a point that indications of AI use do matter with the audience, which goes back to the first two points of AAQCs being a social vetting game. Whatever your own feelings on using AI, the audience and moderator views of perceived AI use matter.

You should understand the arguments against use of LLMs on a discussion forum even if they do not persuade you. I feel @4bpp started a good discussion summarizing AI skeptic concerns, which approach both a moderator and a user concern as the other two endorsing parties. Motte moderators have an interest in encouraging people to put in the effort to contribute, which is undercut if people use LLMs to create longer responses for a fraction of the effort. Individual users can develop their own ‘allergies’ to the tells of AI content, including dislike or boredom just form the signs of editing. Since AAQC writers need an endorsement from both groups, a posting style that could turn off either is an exceptional risk.

Does this mean that no AI can be used in any way in creating an AAQC? No. And sometimes LLM-inclinations to repetition are unavoidable in some formats, like the overlapping /common justifications behind this list of distinct tips to writing AAQCs. But if the people you need AAQC endorsement from are reacting poorly to your use of LLMs to generate or even alter your posts, then you have two general choices. You can ignore their concerns, and hope your post passes muster anyway, or you can tailor your AI use around their concerns. You will not be able to intellectually brow-beat them into endorsing your post if they do not want to, and having a fight over the use of AI is more likely to make ‘neutral’ observers, users and mods both, not want to.

///

Part Four: Topics Of Common Interest (And Honorable Examples)

While individual AAQCs tend towards the novel or atypical, there are broad genres of topics that consistently clear the user and moderator approvals each month. If you, the would-be AAQC writer have an idea but are not sure how to frame it in a way to catch Motte interest, the topics below are historical winners. Not every post along these lines will be an AAQC, but a good-faith and exceptional effort post along these lines has a better chance of being nominated.

/

10: Subject Matter Experts

Tip 10: Wonk In / Nerd Out!

Subject matter experts can write the best ‘depth’ posts by simple virtue of being able to contribute more (and more interesting) knowledge on the (interesting) topic of interest than the layman audience. People know the most about things that they have to know about because it is part of their job, or they love to learn about because it is their passion. Let us call these wonks and nerds, and celebrate both because of what they can bring to any topic.

Wonk-topics tend to be practical, professional, and public-interest issues. Because someone is getting paid to know about them, they tend towards some level of practical and public interest by default, or else no one would be paying for that sort of knowledge. Since the wonk must have a certain level of competence to get and stay hired over time, it implies a certain level of proficiency. With both time and position comes insights into the behind-the-scenes professional perspectives and internal politics that provide those qualities of novelty and insight that make for easier AAQCs.

Nerd-topics may be less elite, but no less interesting. As much as wonkery provides a monetary incentive to go learn an exceptional amount about something, passion needs no other reason. Nerds can dive deep for the strangest of reasons, or no reason at all. Good nerds can bring their wonk skills to other fields to elevate the quality of their passion. Tremble before the nerd who can bring their wonkery or multiple nerd-interests to the same issue, for they can provide unparalleled breadth and depth of effort.

Honorable Wonk AAQC: @gattsuru: "VanDerStok has dropped."

Honorable Nerd AAQC: @UnopenedEnvilope: "Opera! Now this is in my wheelhouse."

/

11: Timelines & Narratives

Tip 11: Tell an interesting story over time.

If subject matter experts provide an easy route to ‘depth,’ posts centered around tracking the narrative of something over time is a straightforward way to ‘breadth.’ Narratives that track a person, group, or dynamic over time by their nature must expand to encompass the other factors impacting the subject of interest. They also take the work that makes it easy to stand out from the rest of the AAQC contenders of the month.

A timeline effort can be a surprisingly literal approach. Take a topic, show how it changed over time, typically with multiple citations of news articles or perspectives at various moments. This style of post stands out because it can connect the limited viewpoints of media coverage in the moment to show how perceptions changed. What was, or was not, mentioned at the time that became clearly obvious / relevant with hindsight? Where are the culture war flashpoints of yesteryear now? These are interesting, but combined in a way that a single perspective at a single point in time fundamentally cannot convey.

A narrative differs by emphasizing the ‘breadth’ of contextualizing something in relation to the world, and less on the developments over linear time. Historic context may matter a great deal, but a narrative approach tends to use the past to explain the present. Sometimes a narrative may be a grand theory of something, sometimes it is just framing (or challenging) how people see the world, but by its nature it is relating a concept to other relevant parts of the narrative.

Honorable Timeline AAQC: @BahRamYou: "Do you remember a short story called "Cat Person," which was published in 2017? It went viral and caused quite a stir at the time."

Honorable Narrative AAQC: @recovering_rationaleist "Someone's wrong on the Radio: Internal contradictions in the narratives on USAID"

/

12: Global Political Developments

Tip 12: The world is filled with interesting things waiting for an interesting take.

Most Motte AAQCs come from the weekly Culture War Roundup thread. While the culture war in question is normally the American one, there are a lot of somethings to be said about cultures and wars elsewhere in the world. Talking about places foreigners are not familiar with, from the cultural viewpoint of a different culture, are easy ways to be novel, outside the norm, and provide that unique je ne sais quoi to seem worldly and experienced. Two approaches of this genre are posts which talk about global cultures, with any conflict being of secondary importance, and posts that cover global conflicts, with culture being secondary.

Talking about global cultures could be anything from an ethnography analyzing a culture foreign to you, to a casual attestation of your experience from within that culture. These topics tend to focus on relating one’s own observations to another frame of reference, whether that be another country or the expectations of an outsider audience. Talking about global cultures leans towards ‘depth’ posting, since you are focusing on a specific aspect of a culture.

Talking about global conflicts can be anything from current geopolitical conflicts to the clash of cultures. The Ukraine War has been a reoccurring topic of the last few years, but intercontinental culture wars, or trade wars, and other conflicts count too. Global conflict posts lean towards ‘breadth’ posting, since you are naturally covering multiple complex states to an audience with a wide range of views of the same issue.

Honorable Global Culture AAQC: @Southkraut: "Such is the dominant discourse in Germany, as imposed by the victors of WW2, and you're getting a taste of it now."

Honorable Global Conflict AAQC: @The_Golem101: "...I think you're making a historical error to include things like the Bengal famine and even the Irish potato famine in with the holodomor uncritically - especially using the same term for both Ukraine and Ireland."

/

13: Popular Culture Media

Tip 13: Truth can be stranger than fiction, but both are interesting.

The Motte has a surprising appetite for discussing media, and not just the reality-covering kind. The culture war touches many parts of culture, of which fiction is as much a part as daily news, and it drives a lot of Motte discussion. Sometimes people want to read about how the culture war affects their media, and sometimes people just want to discuss the culture within their favorite media.

Culture-touching-media posts provide an external viewpoint of the relationship between the real-world culture war and its impacts on the creation and contents of media we consume. These discussions demonstrate the second-order-effects of how the culture war starts to shape not only the people directly involved, but what we later see from them. This approach leans towards breadth over depth, as the separation between culture causes and effects on the media starts to increase the parties and contextual interests.

Culture-within-media goes in for looking at a piece of media on its own terms, often with an internal perspective towards the internal logic of characters, setting, or themes. These takes can generate interest by taking a subjective viewpoint of a setting, then tying in some external IRL factor to give it more salience. This approach leans towards depth over breadth, since it is often a nerd out moment of a specific cluster of personal interests.

Honorable Culture-Touching-Media: @Testing123: "I want to take a break from talking about how modern politics and the culture war is ruining society to explain how modern politics and the culture ruined one my favorite book to movie adaptations: The Long Walk."

Honorable Culture-Within-Media: @self_made_human: "Batman might be a typical Wuxia character. Superman would be a weak character in a Xianxia setting, especially in a novel that is managed to steadily creep up in both power and page count."

/

14: People & Places

Tip 14: Go to interesting places. Learn about interesting people. Tell us about them.

If global culture wars make for good AAQCs because they cover interesting places and people, who needs the culture war? You do not, which is why just talking about notable people or interesting places are regular AAQCs. Even if most of the forum is American, the Motte’s user base is heterodox enough that staying here is already an indicator of interest in different viewpoints from different views and places, making this an easy genre to get at least some interest in.

Notable people posts are some more in-depth introspection or observation about someone notable. Sometimes this can be a way to talk politics or the culture war by talking about a specific politician or culture warrior. Alternatively, it could be a reflection of some personal acquaintance, minor luminary, or something else. These AAQCs will typically make it as AAQCs if they can tie the observations to some broader point, though outright biographies are rare enough that they could work as well.

Interesting places is the AAQC zone where people can be as personal as simply sharing their travelogues or experiences of where they lived. These are the sort of posts that may seem utterly mundane to someone ‘trying’ to think of something interesting, but can be fascinating to outside observers. There are countless local curiosities or observations that may seem mundane to you but make for a distinction to other people’s lived experiences.

Honorable Notable People AAQC: @WhiningCoil: "Never Meet Your Heroes, Even Posthumously"

Honorable Interesting Places AAQC: @aqouta: "Aqouta goes to China", Part 2, Part 3

/

15: Human Experience Stories

Tip 15: Tell us what you think it means to live.

The final genre of AAQCs is the Motte equivalent to the human-interest section of the news media. These are the sort of personal posts that talk about the human condition, or make deeply personal admissions that resonate with the audience. While I do feel obliged to advise everyone to never compromise their internet anonymity for the sake of internet kudos, there is a certain sort of sincerity that comes from trying to untangle the mess of emotions we call the human experience.

Human condition posts are those that muse on the nature of what it means to be and live as a human. Over the years this has included everything from transhumanism, religion, or dating. Everyone has their own human experiences, and thankfully not everyone experiences the full range of human experiences. Writers who can share their own atypical experience with those who have not are contributing to the community sharing that bit more of the human experience.

Personal experience stories are accounts of one’s own lived experience. These can include the sort of viscerally personal confessions of past shames, hard lessons, or humbling admissions that you would almost never hear in public. For all that these are incredibly subjective and non-generalizable, there is a credibility that comes with willingly lowering your guard. While I again never advise anyone make themselves vulnerable to strangers for the sake of internet kudos, some of the people who do so willingly and deliberately are practicing a level of bravery and charity that I will never mock.

Honorable Human Condition AAQC: @FiveHourMarathon: "Taking advice, really taking it to heart and following it, requires a radical act of submission foreign to the modern mind."

Honorable Personal Experience AAQC: @DuplexFields: "Then in November 2010, in my darkest depths, I discovered My Little Pony Friendship is Magic."

///

Conclusion With All The Tips

And with that weighty tip, let us review!

/

The 15 Tips For Writing AAQCs

-

Moderators are the last and most obvious screening party. Less obvious is that they screen in two ways.

-

Some of your fellow Mottizans must find your post interesting. Preferably serial nominators.

-

You are a Mottizan too. Write about what interests you.

-

Basic principles of writing (almost) always apply.

-

Know whether you are trying to go deep or broad, and then be brief on the other part.

-

Write in a way that makes it clear where you are starting, where you are going, and how far along the way you are.

-

Writing in insults is a way to write yourself out of an AAQC.

-

Build a reputation of being more than a single-issue poster by posting on more than a small cluster of issues.

-

The judgement of whether AI improves the quality of your post rests with the audience, not you.

-

Wonk In / Nerd Out!

-

Tell an interesting story over time.

-

The world is filled with things waiting for an interesting take.

-

Truth can be stranger than fiction, but both are interesting.

-

Go to interesting places. Learn about interesting people. Tell us about them.

-

Tell us what you think it means to live.

/

This concludes your fifteen numbered tips on how to go about getting an AAQC, and uncounted numbers within them. Yes, fifteen was an arbitrary number of click bait hook to attract interest. Yes, trying to stick to three supporting paragraphs a tip was an equally arbitrary way to maintain pacing. If you are reading this, then it worked, no?

I would like to give thanks to all the people who helped develop this list. None did so wittingly, and some did so by demonstrating what not to do, but I would not be here years later if there weren’t good eggs here. A shout-out to all the AAQC contributors who were shouted out as honorable examples. There were a lot of good posts this year, and it was a joy to review the last year of roundups. I imagine some of you might be a bit embarrassed for the reminder, but you can blame @naraburns for his diligent effort each month that caught you on record.

Finally, I’d like to leave off by dispelling any absurd suspicions about my motives for this effort. The research behind this advice entailed only the highest quality sources, and was not picked solely from my personal pet peeves and biases. This was always something I planned to do, and not at all a result of being trapped in a series of airports and airplanes during holiday travel. Most of all, any insinuations that I am hoping that this might prompt new or old Mottizans to (keep) writing more of the sort of posts I like are completely unfounded rumors.

I just selfishly want more people to write more and more interesting AAQCs this year, I swear.

This weekly roundup thread is intended for all culture war posts. 'Culture war' is vaguely defined, but it basically means controversial issues that fall along set tribal lines. Arguments over culture war issues generate a lot of heat and little light, and few deeply entrenched people ever change their minds. This thread is for voicing opinions and analyzing the state of the discussion while trying to optimize for light over heat.

Optimistically, we think that engaging with people you disagree with is worth your time, and so is being nice! Pessimistically, there are many dynamics that can lead discussions on Culture War topics to become unproductive. There's a human tendency to divide along tribal lines, praising your ingroup and vilifying your outgroup - and if you think you find it easy to criticize your ingroup, then it may be that your outgroup is not who you think it is. Extremists with opposing positions can feed off each other, highlighting each other's worst points to justify their own angry rhetoric, which becomes in turn a new example of bad behavior for the other side to highlight.

We would like to avoid these negative dynamics. Accordingly, we ask that you do not use this thread for waging the Culture War. Examples of waging the Culture War:

-

Shaming.

-

Attempting to 'build consensus' or enforce ideological conformity.

-

Making sweeping generalizations to vilify a group you dislike.

-

Recruiting for a cause.

-

Posting links that could be summarized as 'Boo outgroup!' Basically, if your content is 'Can you believe what Those People did this week?' then you should either refrain from posting, or do some very patient work to contextualize and/or steel-man the relevant viewpoint.

In general, you should argue to understand, not to win. This thread is not territory to be claimed by one group or another; indeed, the aim is to have many different viewpoints represented here. Thus, we also ask that you follow some guidelines:

-

Speak plainly. Avoid sarcasm and mockery. When disagreeing with someone, state your objections explicitly.

-

Be as precise and charitable as you can. Don't paraphrase unflatteringly.

-

Don't imply that someone said something they did not say, even if you think it follows from what they said.

-

Write like everyone is reading and you want them to be included in the discussion.

On an ad hoc basis, the mods will try to compile a list of the best posts/comments from the previous week, posted in Quality Contribution threads and archived at /r/TheThread. You may nominate a comment for this list by clicking on 'report' at the bottom of the post and typing 'Actually a quality contribution' as the report reason.

Do you have a dumb question that you're kind of embarrassed to ask in the main thread? Is there something you're just not sure about?

This is your opportunity to ask questions. No question too simple or too silly.

Culture war topics are accepted, and proposals for a better intro post are appreciated.

Be advised: this thread is not for serious in-depth discussion of weighty topics (we have a link for that), this thread is not for anything Culture War related. This thread is for Fun. You got jokes? Share 'em. You got silly questions? Ask 'em.

Transnational Thursday is a thread for people to discuss international news, foreign policy or international relations history. Feel free as well to drop in with coverage of countries you’re interested in, talk about ongoing dynamics like the wars in Israel or Ukraine, or even just whatever you’re reading.

The Wednesday Wellness threads are meant to encourage users to ask for and provide advice and motivation to improve their lives. It isn't intended as a 'containment thread' and any content which could go here could instead be posted in its own thread. You could post:

-

Requests for advice and / or encouragement. On basically any topic and for any scale of problem.

-

Updates to let us know how you are doing. This provides valuable feedback on past advice / encouragement and will hopefully make people feel a little more motivated to follow through. If you want to be reminded to post your update, see the post titled 'update reminders', below.

-

Advice. This can be in response to a request for advice or just something that you think could be generally useful for many people here.

-

Encouragement. Probably best directed at specific users, but if you feel like just encouraging people in general I don't think anyone is going to object. I don't think I really need to say this, but just to be clear; encouragement should have a generally positive tone and not shame people (if people feel that shame might be an effective tool for motivating people, please discuss this so we can form a group consensus on how to use it rather than just trying it).

Read this article on Substack for images and better formatting

This article will cover the following:

A summary of where I think AI stands for software developers as of 2025.

-

How much AI has progressed in 2025, based on vibes.

-

A summary of how I’m currently using AI for my work, and an estimate of how much it’s speeding me up in certain tasks.

-

A summary of the top-down attempt from the executives of the company to get people to use AI.

-

How much I’ve seen the other developers that I work with use AI of their own volition.

-

What advancements in AI I’d find most helpful going forwards.

I’ll keep my explanations non-technical so you don’t have to be a software engineer yourself to understand them.

As 2025 comes to a close, it will mark the end of the third full year of the LLM-driven AI hype cycle. Things are still going strong, although there’s been an uptick in the amount of talk of an impending Dotcom-style crash. Basically everyone is expecting that to happen eventually, it’s just a question of when and how much it will bite. AI is almost certainly overvalued relative to the amount of revenue it could generate in the short term, but it’s also clear that a lot of people “predicting” a crash are actually just wishcasting for AI to go away like VR, NFTs, the Metaverse, etc. have done. That’s simply not going to happen. There will be no putting this genie back into the bottle.

Where AI stands for developers

The past few years of using AI to build software have looked something like this:

2023: This AI thing is nifty, and it makes a decent replacement for StackOverflow for small, specific tasks.

2024: OK, this is getting scarily good. Unless I’m missing something, this seems like it will change coding forever.

2025: Yep, coding has definitely been changed forever.

There’s no doubt in my mind that AI is the way that a lot of future coding will be done. This idea was mostly already solidified in 2024, with what I’ve seen in 2025 fortifying it further. The only question is how far it goes. That almost entirely depends on how good the technology eventually becomes, and how quickly. If AI stalls at its current level, then it would only produce a long run productivity increase for coders of 20-50% or so. If it fulfills the two features I discuss towards the end of this article, then it could automate huge swathes of coding jobs and increase productivity by 100%+, but there will still almost certainly be human work to do in interfacing with + building these systems. I don’t foresee a total replacement of SWEs anytime in the near future without a massive recursive self-improvement loop that comes out of left field.

If you’re a developer, you’re shooting yourself in the foot if you’re not using AI to speed-up at least some parts of your job. This isn’t an employment risk now, but it could be in 5-10 years if progress continues at its current pace1. My range for “reasonable disagreement” is the following: on the low end it’s something like “AI is useful in some areas, but it’s still woefully deficient for most parts of the job”, and on the higher end it’s something like “AI is extremely useful for large parts of the job, although you can’t trust it blindly yet”. On the upper end I remain pessimistic about “vibe coding” for anything except the most disposable proof-of-concept software, while on the lower end I respect anyone a bit less if they confidently dismiss AI completely in terms of programming and claim it's just another passing fad. AI is well-within those two extremes.

AI progress in 2025

As for how AI progressed in 2025, results were mixed.

If evaluated from a historical context where technological progress is nearly stalled outside of the world of bits, then 2025 was a bumper year. Indeed, every year since 2023 has seen bigger improvements in AI than in practically any other field.

On the other hand, if we evaluate from claims of the hypester CEOs, FOOM doomers, and optimistic accelerationists, then 2025 was highly disappointing (where’s my singularity???).

From my own expectations that were somewhere in between those two extremes, 2025 was a slight-to-moderate disappointment. There was a fair bit of genuine progress, but there’s still a lot of work to be done.

There were two major areas of advancement: LLM models got smarter, and the tools to use them got a bit better.

In terms of LLMs getting smarter, most of the tangible advancements came in the first few months of the year as reasoning paradigms proliferated with Gemini Pro 2.5, ChatGPT o3, Claude Opus 3.7, and Deepseek taking the world by storm. This happened mostly between January and April2. These were good enough that they could solve basically any self-contained coding challenge within a few prompts, as long as you supplied enough context. They could still make stupid mistakes every now and then, and could get caught in doom loops occasionally, but these weren’t particularly hard to resolve if you knew what to look for and had experience with the tricks that would generally solve them. Comparing the benchmarks of a person using ChatGPT 4o in November 2024 vs ChatGPT o3 in April of 2025:

- SWE-bench Verified: 33.2% → 71%

- Aider polyglot: 23.1% → 81.3%

- Codeforces: 808 → 2724

After this, though, there wasn’t much beyond small, iterative improvements. New versions of Claude, Gemini 2.5 getting tuned in May and June before releasing 3.0 later in the year, ChatGPT getting v5, 5.1, and 5.2 -- none of these had any “oh wow” moments for me, nor did I notice any significant improvements over several months of use. I’m playing with Sonnet and Opus 4.5 now, and they’re… maybe a small step up? I’ve noticed it will correctly ask for additional context more often rather than hallucinate as weaker models tended to do, but this might also be explainable by me just improving my prompts. I keep up with model releases pretty well, and I see their benchmarks continuing to slowly rise, but it doesn’t really feel like I’m using a model that’s obviously smarter today in December 2025 than I was from April 2025. Obviously this is all highly anecdotal, but vibes and personal use are how a lot of people primarily judge AI.

Part of the issue is almost certainly diminishing returns. Would it make that much of a difference if LLMs could code some feature in an average of 4 reprompts instead of 5? It’d probably be useful if you could consistently get that number down to 1 for all coding tasks as you could then trust LLMs like we do for compilers (it’s very rare for a dev to check compiler output any more). But getting AI to that level will take exponentially more work, and I doubt it will be doable at all without unhobbling AI in other ways, e.g. automating context management instead of relying on a human to do that.

The other major area of improvement was in the tools to use these LLMs, and by that I’m talking about AI “agent” tools like ChatGPT Codex and Claude Code. These are glorified wrappers that are nonetheless useful at doing 2 major things:

- They edit code in-line. In 2024 most people relied on copy+pasting code from the browser-based versions of LLMs, which caused a number of problems. Namely, either the AI would slowly regenerate the entire program each time there was a single alteration which would take forever and burn a bunch of tokens, or they would only regenerate parts of the code and thus rely on the user to selectively copy+paste the updated code in the right locations, which caused an endless series of headaches whenever there was a mistake.

- They have a limited ability to go out and find the context that they need, assuming it’s relatively close by (i.e. in the same repo).

I don’t want to undersell the usefulness of tools like Claude Code, as those two things are indeed very helpful. However, the reason I called them “glorified wrappers” and put the “agent” descriptor in quotation marks is because they’re still extremely limited, and aren’t what I had in mind when people were talking about “agents” a year or two ago. They cannot access the full suite of tools a typical fullstack engineer needs to do his job. They cannot test a program, visually inspect its output, and try again if things don’t look right. Heck, they don’t even do the basic step of recompiling the program to see if there are any obvious errors with the code that was just added. When people discussed “agents”, I had something in mind that was much more general-purpose than what we have right now.

Both Sam Altman and Jensen Huang stated that 2025 would be the “Year of AI Agents”, but this largely did not happen at least in terms of general purpose computer agents. There were a few releases like Operator that generated some buzz earlier in the year, but they were so bad that they were functionally worthless, and I’ve heard very little in the way of progress since then. I feel this is a bigger deal than most people think, as it’s almost certainly necessary (though not sufficient) for AI to have at least mediocre skills in general computer use for it to break free of the rut of short time horizons tasks it’s currently stuck in.

AI on the job in 2025

Below is a chart of the tasks I do as a software engineer, how helpful AI is in completing them, and the approximate percent of my working hours that I spent on them in 2020 vs today. My job over the past year has been in modernizing a reporting tool that our Research team uses for statistical releases. The old tool was designed in the 90s using SQR and Java Swing, i.e. it’s two fossils duct-taped together. My job is to modernize it to SQL and React.

| Task group | AI utility out of 10 | % time in 2020 | % time in 2025 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gathering requirements and useful meetings |

0 | 5% | 5% |

| Pointless meetings | 0 | 10% | 10% |

| Translating SQR to SQL (backend) |

7 | 50% | 25% |

| Creating the frontend | 8 | 15% | 10% |

| Creating the Excel templates |

2 | 10% | 15% |

| Dealing with the middle “guts” (service layer, service email, etc.) |

3 | 5% | 15% |

| Dealing with server issues |

4 | 10% | 20% |

Gathering requirements and useful meetings: AI is not helpful here since I need to know how I should be designing things, and that’s just most easily done by being present and asking questions. Perhaps I could use AI to help take notes, but that seems like more of a hassle than its worth so far.

Pointless meetings: AI is also not helpful here since these are socially enforced. Every day we have a completely unnecessary 30-45 minute “standup” (we are always sitting) where we go around the room with all the devs explaining what they worked on to the manager, like a mini performance review. These often devolve into debugging sessions if any task takes longer than a day. I think the manager is trying to offer helpful suggestions, but the way he phrases things always makes it sound like thinly veiled accusations that people aren’t working fast enough. He also has no real idea of the nuances of what people are working on, so his suggestions are almost always unhelpful. God I hate these meetings so much.

Translating SQR to SQL: In 2020 this would have been by far the bulk of my work. This is where the logic for the reports is, and AI has been a massive help. AI has been so good that I’ve just never bothered to learn much about SQR -- it’s close enough to SQL that I can get the gist of it, while any of the more complicated bits can be dealt with by the LLM. AI can often one-shot the data portions of the logic, although it has trouble with the more ad-hoc formatting bits. The reason I give this a 7/10 instead of a 10/10 is because my human skills are still needed to give context, define the translation goals, break compound reports into manageable chunks, reprompt when errors occur, and press the “compile” button. I’m more of a coordinator while AI is the programmer, and as a result I spend a lot less time on this part than I would otherwise need to.

Creating the frontend: AI is also quite helpful in wiring up the frontend. We have less ad hoc jank here which typically means less reprompts are necessary, but my human skills are still required to give context, press the “compile” button, etc.

Creating Excel templates: The people we’re creating reports for are very particular about the formatting, which means AI isn’t very helpful. I’ve tried it a few times, but it’s just faster to do things myself to get the exact bolding, column widths, etc., though AI is good at giving conditional formatting formulas. Since AI has sped up the coding parts I’ve ended up working faster, which means I end up spending a greater percentage of my time on these.

Dealing with the middle “guts” and Dealing with server issues: The servers and the middleware “guts” are a tangled mess of accumulated cruft solutions that have built up over the years. Before AI I would have tried to avoid touching this stuff as much as possible, but now it’s much easier to understand what’s going on and thus to make improvements. If the servers go down (which is very frequent) I can try to proactively fix the problem myself. I’ve also played around with Jenkins to automate some of the server redeployments, and learned how to pass info through the various layers to tell if something is going wrong. This stuff is too tangled and spread out over different repos for a tool like Claude Code to automate anything, but LLMs can at least tell me what’s going on when I copy+paste code.

Overall, I’d estimate my work speed has gone up by about 50%. That’s spread out over 3 main areas:

- 10% working faster and doing more.

- 20% spending more time to design more robustly, avoid tech debt, and build automation, mostly in the middle “guts” and server areas.

- 20% dark leisure -- most of this article was written while at work, for instance.

Management’s push for AI

As the executives at the company I work for have tried to implement AI, they’ve done so in an extremely clumsy way that’s convinced me that most people have no real clue what they’re doing yet. If what I’ve witnessed is even somewhat representative, then the public’s overall understanding of AI is currently at the level of a senile, tech-illiterate grandma who thinks that Google is a real person you ask questions to online rather than a “search engine”. Even something as basic as knowing ChatGPT has a model selector with this thing called “Thinking” mode easily puts you in the top 10% of users, perhaps even the top 1%.

Upper management is plugged into whatever is trendy in the business world, and AI is certainly “in” right now. The CTO (with implicit pushing + approval from the rest of the executive team, especially the CEO) is heavily promoting AI use, but this seems destined to be mostly a farce for the usual reason that all bandwagony business trends tend to be -- saying the firm is “using” is the goal moreso than any extra efficiency it can give. Oh sure, they’d happily take any extra efficiency if it was incidental, but it’s not really the primary focus. This acts as one of the most powerful anti-advertisements for AI use among the developers where I work. Fads like low-code tools or frameworks like CoffeeScript come along perennially and almost always disappoint. It’s no wonder that many devs instinctively recoil when a slimy MBA comes in who clearly doesn’t know much about AI or programming, and starts blathering on with “let me tell you about the future of software development!” We’ve seen it all before, so now whenever I try to sing the praises of AI I have to overcome that stench. “No really, AI is a powerful tool, just ignore how management is trying to hamhandedly shove it into everything including places it obviously doesn’t belong”.

Since I’ve become known as the “AI guy” among the developers, I got put on the CTO’s “AI working group” -- basically a bunch of meetings twice a month where we discuss how AI could be implemented across the organization. I tried to go in with an open mind, but that didn’t last long.

Meeting 1: The CTO gathers the developers and asks for input on what AI tools we could augment the development stack with. He mentions examples including Github Copilot, Claude Code, and a few others. I express strong interest in Claude Code as I’ve heard good things about it, while another dev chimes in to back me up. The CTO responds with “interesting perspective… but what have you heard about Copilot?” It becomes clear that the meeting is consultation theater and that his mind is already made up -- he tells us he’s attended several conferences where Copilot was mentioned favorably and he has a bunch of promotional material to share with us. I ask if we could try both Copilot and Claude Code, but that idea is also shut down. I do some research on my phone and discover that Github Copilot is just a SaaS Wrapper with the useful models locked behind “premium requests” that you have to pay a subscription to access. The difference is between a model like Sonnet 4.5 on the premium side vs ChatGPT 4o-mini for the free version, which if you’ve played around with those models you’d immediately know there’s a vast gulf in capabilities there. I ask if we can get the business license to use the advanced models, and the CTO asks if the advanced models are really necessary. I cringe internally a bit, but convince him that they are, and he agrees to get the business licenses.

Meeting 2: The CTO gathers 2-3 employees from each department of the company for us to discuss how each of us is using AI in our day-to-day work environment. Well, at least that’s ostensibly what was supposed to happen. In practice it becomes an entire hour of introductions and each of us giving a little blurb on what our overall opinion is on AI. Basically everyone says some variation of “It sure seems interesting and I look forward to hearing how other people use it” without anyone actually saying how they use it beyond the most basic tasks like drafting emails. The only interesting part was when one of the employees said she hopes we can minimize AI use as much as possible due to how much power and water it uses. The CTO visibly recoils a bit on hearing this, but collects himself quickly to try to maintain that atmosphere of “all opinions are valid here”. I cringe a bit internally since the bit about water usage is fake, but I know the perils of turning the workplace into a forum for political debate so I say nothing.

Meeting 3: The CTO gathers the 2-3 employees per department and announces an “Action Plan” where the company will be implementing a feature that will allow us to build our own little mini Copilots that have specific context in them. He requests that each of us comes up with 2-3 use cases for where these could be utilized. These are using tiny models that will be worthless for coding so I mentally check out.

Meeting 4: This meeting involves the details of the “Action Plan” but I strategically take a vacation day to miss it.

How I’m seeing other developers (my coworkers) use AI

Despite the executives’ clumsy attempts with a top-down approach, I’ve seen a decent amount of bottom-up usage of AI among the developers that I work with, though it’s highly stratified.

Older dev #1: This guy is a month or two from retirement. He’s shown approximately zero interest in using AI himself, although he’s been impressed when he’s seen me use it.

Older dev #2: This zany individual has since left the company. He was, for some reason, a big fan of Perplexity -- an AI tool that I’ve heard very little positive feedback about from anyone else. Beyond this, he tried using AI to solve a difficult coding challenge (likely one he didn’t want to deal with personally), but a combination of 1) it being a tough problem, 2) him using a weak (free) AI model, and 3) him not being particularly experienced in aspects like how to break down a problem for AI and how to give it the right amount of context, all combined to produce an unsatisfactory result. After this, he mostly dismissed AI in the software world as any other passing fad.

Middle age dev #1: This guy is probably the most skilled dev out of all of us has tried using AI at least a little and had a few positive stories to share about it, but it seems to be something he’ll only use occasionally. When we were debugging an issue together, his first instinct was the old method of Google searching + StackOverflow like it’s still 2020.

Middle age dev #2: He has shown some interest in using AI, but has little gumption to do it himself. He asked me for advice on using AI on a problem he clearly didn’t want to deal with since it was long and complicated. I told him that AI would probably only give middling results on a task like that, to his disappointment. I’ve seen very little AI use after this.

Middle age dev #3: I’ve seen him use AI a little bit here and there, but mostly just for debugging things, not systematically to generate code.

Middle age dev #4: He’s basically using AI as much as I do. I’ve asked him his opinions on the subject, and they’re a close mirror to my own -- he thinks AI is here to stay, but he’s doubtful of things like vibe coding. He subscribes to the $100 plan of Claude, and I see him using Claude Code almost all the time.

Younger dev #1: I see him using AI a decent amount, although it seems somewhat unsophisticated -- he’s been using the Github Copilot trial that the CTO pushed for. A lot of the time savings seem to be going towards dark leisure.

Manager: He’s tried to use AI out of what seems like pure obligation -- partially from the CTO pushing down from above, and partially from also being plugged into the MBA zeitgeist that’s saying that AI is trendy and implicitly that anyone who isn’t using it will “fall behind”. He offhandedly mentioned how he tries to set aside 30 minutes per day to test out AI, but the features he’s most excited about are extremely basic ones like voice mode and the fact that ChatGPT retains some basic memories between conversations. When he complained about hallucinations in a particular instance, I asked him what model he was using and he reacted with total confusion. Then we went to his screen and he was on the basic version of ChatGPT 5 instead of ChatGPT 5 Thinking, and I had to explain the difference -- so he’s not exactly a power-user.

Wishlist #1 for AI development -- more context!

One of the most critical aspects of programming with AI is managing its context window. LLMs learn pretty effectively within this window, but long conversations will rack up usage on your daily allotment or your API costs rather quickly. You want to start new conversations whenever you’re done working on a small or medium sized chunk of your program to flush out the old context and keep everything chugging along smoothly. When you start a new conversation, you’ll need to supply the initial context once again. In my case I keep several text files that have general guidelines for how the AI should approach the frontend, the backend, various connector pipelines, etc. Then I supply the latest version of the relevant code, which can span across multiple files that I’ll need to manually select based on whatever feature I’m adding. Finally, I’ll need to tell the AI what I want it to build and the general gist of how that fits into the code I just supplied. All of this navigating around and thinking about what info should be added vs what should be omitted takes time. It’s not a huge amount of time, but it’s not trivial either -- of the time I spent manually coding previously, I’d reckon I spend about 15% of my time now supplying context to the AI, and 85% working with the code that it spits out (integrating it, debugging it, reprompting if it’s wrong, etc.)

Problems arise if I get this wrong and don’t supply enough context. The AI will hallucinate in random directions, sometimes adding duplicative functions assuming they don’t exist, while other times it tries to rely on features that haven’t been created yet. The outcome of this is never catastrophic -- usually the code just fails to compile -- but it can waste a surprising amount of time if the issue only breaks at one critical line halfway through the generated output. If I’m being lazy and just copy + pasting what the AI is churning out, I’ll get the compiler error and copy + paste that back into the AI expecting it to fix it, which can lead to several rounds of the AI helplessly trying to debug a phantom error of a feature that doesn’t exist yet. Eventually either I’ll read through things more closely or the AI will figure out “hey wait, this function is totally missing” and things will be resolved, but this can take 15 or 30 or even 45 minutes sometimes. If you include the time I spend managing context, along with all the issues I have to resolve with not supplying the right context, then that 15%-85% split I mentioned in the previous paragraph can look more like 35%-65%. In other words, on a particularly bad day I might spend more than 1/3rd of my productive time just wrangling with context rather than actually building anything.

Some of this is just on me as a simple “skill issue”. I should be less inattentive both in supplying context and in checking what the AI is pumping out. But on the other hand, if I exhaustively proofread everything the AI does then that would destroy much of the time savings of using AI in the first place. There’s a balance to be struck, and finding that balance is a skill. If we were in a scenario where LLMs stalled out at their current capabilities as of 2025, I doubt I’d ever completely eliminate making mistakes with managing context for the same reason it’s unrealistic for even experienced developers to never have bugs in their code, but I’m confident I could get it below 20% of my productive work time.

<20% isn’t that much, but I think this still underestimates the time lost to managing context for one final reason: it’s boring, and that makes me want to do other things and/or procrastinate. Managing context mostly just consists of navigating to various files and copy + pasting chunks of code, then writing dry explanations of how this should fit together with what you actually want to build. It’s not difficult by any absolute metric, but it’s fairly easy to forget one important file here or there if you’re not paying attention. Starting new AI conversations becomes a rupture in the flow state, which gives my brain the excuse to think “Break time! I’ll check my emails now for a little bit…” And then that “little bit” sometimes turns into 60+ minutes of lost productivity for normal human reasons.

Obviously this is a willpower issue on my part. But it’s also not particularly reasonable to demand that humans never procrastinate, especially on boring, bespoke tasks. My preferred solution to this issue would just be for someone else to fix the problem for me.

If we had unlimited access to infinite context windows, this entire subset of problems would basically disappear. Instead of needing to flush out the context every so often, we could just have one giant continuous conversation. Instead of strictly rationing context piecemeal for any given request, we could just dump the entire source code into the AI and let it sort itself out.

The fantasy of an infinite context window is fairly analogous to the idea of AI agents that are capable of “continuously learning”. We’re probably several years if not a decade+ away from a robust version of that. However, even moderate increases in usable context window sizes would still be very helpful. A usable context window that was twice as big would mean we’d need to refresh conversations half as often, which would mean half the time spent on supplying context, half the chances to screw up and provide too little, and half the opportunities to procrastinate on the issue. An order-of-magnitude increase could mean that large codebases only need 3-6 conversations going for each of its broad areas, rather than needing 30-60 separate conversations for each feature.

It almost feels like a fever dream that ChatGPT 4.0 launched with a context window of just 8K tokens back in early 2023, with a special extended version that could accept 32k tokens. Today, ChatGPT 5.1 and Sonnet/Opus 4.5 both have 200K+ context windows, while Google Gemini 3.0 advertises 1 million.

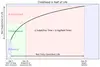

But it should be noted that just because they advertise something doesn’t mean it’s necessarily true for practical purposes. I used the term “usable context window” a few times, which depends on 2 main factors:

- How good the compression algorithms are. From my limited research, it appears that context windows follow an O(N2) relationship, i.e. increasing context by 10x requires ~100x more compute, which is brutal. To get around this, model developers use tricks like chunking, retrieval, memory tokens, and recurrence to compress past context into a smaller representation. This allows for larger context sizes, but comes at the cost of making in-context elements “foggy” if the compression is too aggressive. Companies could advertise a context window of 10M or 100M, but if the details from 100K tokens ago are too compressed to be usable then that wouldn’t be worth much.

- How much access end-users actually get at a reasonable cost. Longer conversations with more stuff in the context window use more resources, which model providers meter with increased API costs and daily allotment usage. I recently had an exceedingly productive conversation with Claude Sonnet on a long and complicated chunk of code that was almost certainly near the limit of the context window, and each message + response took a full 10% of my 6-hour allotment on the $20/month plan. Even if the model’s recall is perfect in a 10M context window, if companies charge an arm and a leg to use anything past 500K then 10M once again doesn’t mean much to the average user.

It’s almost certain that LLMs will continue to get cheaper over time. There’s a very robust trend towards more cost-efficiency per performance, so that half of the equation should continue to improve rapidly over the next few years.

As for how big the context windows will grow, that part is much less clear. I would expect it to get better, but not necessarily at a Moore’s Law exponential rate. The O(N2) relationship is the stick-in-the-mud here, and I’d expect lumpy jumps from time to time when there are breakthroughs in compression algorithms, or if companies feel they have sufficient compute to eat inflated costs.

But there’s also somewhat of a case for pessimism on the rate of improvement, as it feels like context is getting a lot less attention than it used to. Part of that might be due to how most casual users won’t need super huge context windows unless they’re doing some crazy long RP session over multiple weeks. Context limits used to be highlighted metrics when new models were released, but many new models don’t even bother mentioning it at all any more. This feels strange when there are some very goofy benchmarks like Humanity’s Last Exam that get cited almost every time there’s a 1-2 point improvement. The only benchmark I know of that tests context recall is Fiction Livebench which is questionably designed and rarely updated -- as of December 2025 the latest results are from September 2025, with many of the most recent models not listed.

The days of 8K token context limits feel similar to when video games in the 80s had to be compressed down to just a few hundred kilobytes (e.g. Final Fantasy 1 was less than 200 KB). In just a few years we’ve entered the equivalent of the megabytes era, which is a lot better but is still quite restrictive in a lot of ways.

Wishlist #2 for AI development -- better general computer use.

The other innovation that would substantially improve AI coding at this point would be for the AIs to learn how to use computers like humans can. There was quite a bit of noise around this in late 2024 with Claude and in early 2025 with Operator, but the consensus at the time was that they were both terrible. They were at the ChatGPT2 era of functionality that could sometimes do something useful, but relying on them was a fool’s errand.

Since then, we haven’t heard much in the way of progress. Gemini had a version of computer use in October, but it was mostly focused on browsers and still wasn’t very good. General computer use agents are still broadly worthless as of year-end 2025.

Competent general computer use would be extremely helpful for moving between various layers of software. Most nontrivial modern applications end up being a horrible Frankenstein monstrosity of many different frameworks that each deal with one specific issue. Software developers have euphemistically come to refer to this as a “stack”. For a basic example, a customer who logs into a site will see the frontend in a language like Javascript, while validating their login credentials and serving account details is dealt with a backend in a language like SQL.

In practice, just having 2 parts like this is VERY conservative. For a more realistic example, I’ll go with what I’m working on at my job. I’m rebuilding an internal app for statistical data that needs to Create, Read, Update, and Delete entries. It’s a bit more complicated than your average CRUD app, but at the end of the day it’s still just a CRUD app -- it’s not exactly rocket science. Yet even for this, I have to deal with the following:

- Monthly: The frontend.

- service-layer: An interstitial layer that routes most of the info from the frontend to the backend.

- azure-sharepoint-online: Another interstitial layer that routes some info from the frontend to the backend.

- service-reports: This receives calls from the backend and packages them into formatted excel reports.

- service-email: This emails finished reports to the end-user.

- The backend to query data goes through TSQL, which we build and debug with an IDE called DBArtisan

- The formatting of reports happens through a package called Aspose, which turns TSQL results into an Excel format

- The Excel sheets themself also require a bunch of manual formatting for each report.

- Jira tickets for documenting work

- Bitbucket for source control, and navigating between 3 different environments of DEV, TEST, and PROD.

- The internal server that hosts this app runs off of a Linux box and Apache Tomcat.