domain:mattlakeman.org

Same vibes as my series (is three a series?) of "unenviable lives" posts,

I'd really like to see more of this sort of content in the way that you've delivered it. This is how people are and how they live. Many of us didn't grow up in those environments so 'we' need to have more data points like this to see how people really live. I've had a lot of unpleasant experiences (and some pleasant) with the working and underclass, but no one really talks about it in depth.

Separate to this, I think its a disservice how Anthropologists and Sociologists veer away from 'unpleasant truths' in how they present their research.

Until that point, it's manic pixie dreamgirl paradise.

I'm glad you've learned your lesson. I'd never ever fall for this trap.

The immortal words of Mike Tyson about being punched in the mouth.

Hmm, yes, I see.

You may not think it's true, but you certainly act as if it's true.

We can all look at your posting history and note that you are not spending your time denouncing or distancing yourself from any given stupid comment by any given political figure. Despite your constant failure to distance yourself from the infinite stupidity of the universe, it would, in fact, be unreasonable to claim that said stupidity represents you to any relevant degree.

Also, the reveal of Quirrell's true identity caught a lot of people off guard.

Seriously? I haven't even read the original books, but wasn't that, like, the plot twist of the first volume?

So let me get this straight: he's covered literally to his head in tattoos, he sells drugs, he's a drunk and a junkie, he's violent with the criminal conviction to back that up, and he just straight-up violently murdered a guy with a samurai sword over a disputed drug debt. But he's such a loving partner and father!

The contradiction is not as irresolvable as it may, at first glimpse, appear; it is far more common than one would assume that someone will be benevolent to their family or close associates, while displaying unbounded cruelty to those they have convinced themselves deserve it.

This cuts across distinctions of personal appearance; the same pattern, with substitution of variables, describes the Nazi concentration-camp guard ('he's a sub-human weakening the Aryan¹ Race'), the Soviet gulag guard ('he's a wrecker trying to derail the Revolution on behalf of the capitalists'), the United-Statesian ICE agent ('he came into our country rather than obey our command that he quietly starve or be murdered in his place of birth'), the person of hair colour and pronouns in the cancel-mob ('he's a cishet-white-male schistlord who used a term² on the naughty-no-no-word list') and the seller of disfavoured substances ('he didn't pay me the money he owed me, thus violating the Non-Aggression Principle').

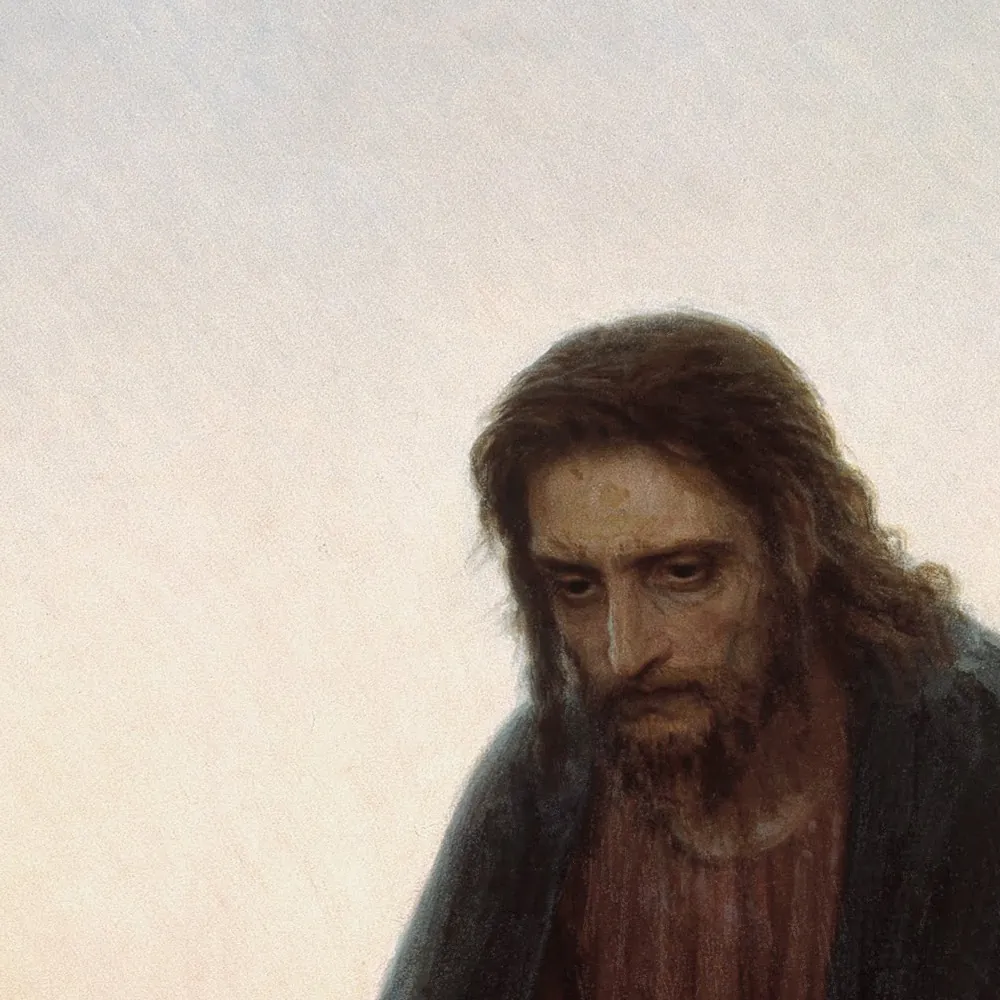

Focus less on "Which personal aesthetics mean that this person is or isn't safe to associate with?" (cf. Goodhart) and more on the Parable of the Good Samaritan³, as interpreted by Fred Clark. (Patheos, April 2017)

¹...despite him being of Romani origin, and thus more Aryan than the Germans.

²...which was actually the preferred nomenclature five years ago.

³If Jesus were telling the story today, would it be the Good Palestinian?

I just don't think that's true. If AOC says something like "abolish ICE" and a decent chunk of the Democratic party waffles as to whether they agree, then it's reasonable to say that a decent chunk of the party is at least sympathetic to the idea, even if they don't explicitly endorse the literal statement.

I don't get your point about "the establishment" in this particular context. Why does it matter if they have power (real or perceived) in regards to whether it's a specific or general group. Most people, even politicians, don't see themselves as "establishment". For some people, Trump as POTUS is the epitome of "establishment". For others, calling him that word is utterly ludicrous. Note that I personally think it's fine for people to attack "the establishment" -- I'm opposed to this rule in general.

And I'm not defending his post wholesale -- I agree the last bit is presumptuous and I'm fine with him being given a warning for something like that. I don't think throwing the gauntlet to someone like this is really that bad, but maybe I'm in the minority on that. I think personal attacks are far worse for productive conversations, which happen regularly and don't get punished (or even become AAQCs!) as long as it's someone with a right-wing opinion attacking someone with a left-wing opinion.

I also have some reservations with how it seems like a final warning from stuff like his previous post which didn't deserve a mod action at all.

I just watched the film. I couldn’t stop imagining how poorly received it would be with any other race combination.

A Bavarian beer hall gets set upon by Jewish vampires who menace the Germans with renditions of Hava Nagila.

A honky tonk besieged by a group of black vampires who blast hip hop and crip walk.

An English pub boarding itself up against Muslim vampires who are broadcasting a call to prayer and unfurling prayer rugs.

It is still weakmanning to insist that [someone] else speaks for [group X] because arbitrary-subjective sections of [group X] weren't sufficiently vocal in denouncing [someone].

Its really hard to believe that you or anyone would actually hold this position.

if you are as racist as you claim, then surely you would prefer to live in a place where all jobs were done by white people, if only because it would mean that you would only have to interact with white people. But instead your position is that for abstract reasons, it offends you to allow white people to do manual labor, so its better to import brown people to do it, even though it means that you and your friends and family have to interact with brown people all the time? And you now risk brown people becoming a meaningful voting block in your society that can never be expunged. Like it would be one thing if you said you were in favor of the migrant work laws used by UAE and not america, or you like rhodesia, but your position doesn't seem to be divided like that. Those of us who live in the modern west, live in the modern west. Is you position based on a fictional alternate reality?

Your position seems really counterintuitive. I strongly suspect you are lying because your stated beliefs and policies are so wildly out of sync with each other - when taking into account the real world as it exists now.

The middle ground is modern medicine is good enough to save people who 10 years ago would have been pronounced dead almost immediately upon arriving at the hospital, but even fully replacing a humans blood capacity several times over can't save them from brain death.

Laddie, you posted the incident where the American leftwing actors were willing to risk 10 years or more in federal prison for an attack on ICE agents. You have been provided a decade-long historical example of magnitudes more than 10 people were willing to suffer far worse than 10 years in jail. Are you really going to try and insist that not even 10 of their rightwing equivalents would draw the line at a lie?

I'd say false flags are much, much, different from "riding out to meet them", which is what I imagine this situation would be for a left winger. "Let's do something (we consider) evil and deranged, to show how evil and deranged the outgroup is" as you're perfectly aware you're doing the evil/twisted thing, and not the outgroup, requires a much more twisted mind. It's not impossible, there have been people that talked themselves into believing that the outrgroup is terribly evil, but managed to hide their true nature from the normie, that all bets are off, and any tactic is justified. Intelligence agencies and militaries can pull it off regularly, because they can promise impunity and recruit from the pool of amoral sociopaths. An idealist with a mind so twisted is much less likely, and getting 10 of them together would require they all be part of a cult, imo.

Didn't we just have this conversation the other day about beards?

I would never get a tattoo and have judgements about tattoos but this doesn't really indicate that tattoos are a red flag. I mean, they are. But this goes well beyond that. There's a big difference between a tattoo of a bird on your arm, and what this person has which is the equivalent of having "I am an insane and dangerous person" tattooed across your forehead.

Back to my main point: people covered in tattoos and/or piercings are the human equivalent of aposematism, change my mind.

Does anyone who isn't a full on progressive zealot disagree with you that a person tatted up that that guy is probably bad news? I really doubt it. And the progressive zealots actually agree with you too, they know that person is bad news, they just see protecting and creating people who are bad news as a core goal.

I honestly don't know why some women are so stupid. Yeah, loving and devoted up to the minute he swings at you with a sword, you silly girl.

They're not stupid. They know that they are flirting with genuine danger. That's the appeal.

You think you could find 10 right-wingers or just mercenary guys willing to do 10 year in federal prison, on a lie?

Laddie, you posted the incident where the American leftwing actors were willing to risk 10 years or more in federal prison for an attack on ICE agents. You have been provided a decade-long historical example of magnitudes more than 10 people were willing to suffer far worse than 10 years in jail. Are you really going to try and insist that not even 10 of their rightwing equivalents would cross the line at a lie?

Go to a serving infantry soldier and tell him LMGs are 'tacticool'

An AR-15 modified for an automatic rate of fire is not a LMG. People pretending they are the same would very much fall under the tacticool coolaid.

and 'not actually very useful'.

Spraying and praying beyond effective range not being very useful is why doing so is often teased / mocked as playing Rambo.

AR rifles are fairly controllable in full auto, and with a bipod they're probably extremely controllable.

If all you mean by 'fairly controllable' is 'in the general direction,' this would be missing the point, much like firing at full auto at the ranges of this incident.

Whoever they'd have been shooting at would have been dead. Swapping out mags isn't that hard either.

Unless they missed because they were playing with full auto beyond the effective range of auto. Like what happened in Texas.

Is ridiculously selectively applied, e.g. basically any time people use "the establishment" as a foil they're guilty of this, but they don't get modhatted. As it stands, the rule is merely another cudgel to use against people making left-leaning arguments

The difference being that "the establishment" is meant to specify the criticism to the people with actual power, rather than generalize to everyone who might hold a particular view, and expecting them to defend it. For example, even though you call yourself "The Antipopulist" I would not lump you in with the establishment, and I would not demand that you, personally, defend the establishment's more controversial views and actions (unless there's something we don't know about you, and your position in mainstream institutions).

As for the claim that moderation has become asymmetrical in an anti-left direction, I'm trying to keep an open mind, but you're not helping. You listed several examples of "bad posts" the last time this was brought up, and while I can agree there was something bad about them in that they contained heat that could be taken out to leave more light, you went on to defend posts that were much, much worse, and you're continuing to do so here. One of your examples was "outgroup politicians are 'foreign agents'", but the actual post is much closer to "Ilhan Omar is a foreign agent".

Like I said, I don't even mind having Turok around, he's mostly an asset for people like me. The only downside of his presence would actually affect people on the left than people on the right - his tone is contagious. You said you want moderation applied equally to everyone, well if he gets to post the way he post, and the same standard gets applied to the median motteposter, the level of aggression on this forum is going to rise substantially, and the quality of discussion is going to drop, and you'll again be distraught about how much the right-wingers are getting away with.

Because up until that point, they think it's hot that he could attack other people with a samurai sword, but he could never do that to them because he just loves them that much / they alone have the power to tame him / he's so emotionally dependent on them that his world would collapse without them / insert-their-preferred-framing-here.

You and most other posters on this thread seem to think that women are only interested in dangerous men being dangerous to other people and are obviously in denial about the possibility that dangerous men are dangerous to them. I don't see any reason to assume that. Why can't women (well some women, I'm not a believer in the redpill position that all women. are the same) be actively attracted to men that are dangerous to themselves. I don't really think that the women that feel a strong attraction of total lunatics like this (as opposed to the normal attraction to bad-ish boys) are deluded about the fact that they may themselves be harmed by them, in fact that may add to appeal. Plenty of men and women like to jump out of planes or free climb, I don't see why these women have to be lying to themselves about danger to involve themselves with dangerous men.

people covered in tattoos and/or piercings are the human equivalent of aposematism, change my mind.

In some cases and otherwise to some degree, yeah. Tattoos signal any of the following:

- Stupidity

- Short-sightedness

- Addiction

- Insecurity

- Bad taste

- A desire to fit in

- A good sense of what is currently fashionable

Nobody will ever convince me that the one-billionth "tribal" tattoo or chinese lettering down the spine of a non-chinese-speaker is meaningful or artistically valuable.

Most people look like either a toddler slapped stickers on them, or like a derelict wall in a shit part of down.

as @Iconochasm said. Hits the nail on the head.

All you have done is clearly demonstrate that you have already made up your mind and no matter what hoops people jump through will not be sufficient.

first you lie

you would not bother to engage with and would dismiss it all out of hand

All you have done is make me update towards you also being a net-negative.

Yeesh, no thanks.

If AOC says something and isn't broadly getting a lot of pushback from her party, that would be quite indicative that at least a major fraction of the left believed something, or at least doesn't disagree with her. This is not weakmanning.

You're broadly correct here: the anti-immigrant right (or "racialist Right") definitely don't regularly push back against claims that legal Americans would be willing to do those types of jobs. If they did, it would undercut their position that we should do mass deportations, so they either ignore it (like Catturd and friends) or they say legal Americans would do it if the price is right. The people claiming you're strawmanning Republicans in this specific post are hard to take seriously.

Sailors' tattoos were also earned e.g. a swallow meant you'd sailed 5000 miles. It wasn't all just covering yourself in random pictures.

We should wait for audio analysis. The timing of the switches being turned off critical. To the precise millisecond.

More options

Context Copy link